The Senses

The Senses

Our senses help us experience the world around us. Harvard researchers are working to understand, improve, and replicate these sensory organs.

The ins and outs

The act of sensing starts with stimulus from the world, which triggers a physiological response, which is combined with previous experiences, which results in an internal representation, which is our brain’s best guess at what’s going on around us.

Eye of the beholder

Vision is so much more than meets the eye. By absorbing and assigning colors to a small piece of the electromagnetic spectrum, we can discover beauty, danger, and opportunities all around us.

Making sense of how people who are blind ‘see’ color

Harvard researchers have found that despite experiencing color differently, both blind and sighted people share a common understanding of the concept.

Demystifying dyslexia

Neurologist Albert Galaburda discusses what brain clues and neurodiversity reveal about reading challenges.

Pursuing gene therapy for progressive blindness

Harvard researchers studying Usher syndrome type 1f are exploring three different options for restoring vision in those affected.

How common is face blindness?

The inability to distinguish between faces, or prosopagnosia, may impact more people than previously thought.

Hummingbird senses

Unlike many birds, which have no taste receptors for sweetness, hummingbirds evolved to detect sweetness nearly as fast as a beat of their wings.

The touch, the feel

If you’ve ever been curious about how the body experiences cold, heat, pain, and pleasure, touch research may help scratch that itch.

Touch is much more than just conscious perception of what you are actively reaching out to feel, or what is touching your skin.”Professor of Neurobiology David Ginty

Why are certain body parts so sensitive?

There’s the rub

Harvard researchers are exploring the causes and possible solutions to itchy skins, including poison ivy’s molecular path in the body and a common skin bacterium—Staphylococcus aureus—which can cause itch by acting directly on nerve cells.

Magnetic senses

A family of light-sensitive proteins called cryptochromes, located in the retinas of animals like fish, amphibians, and birds, may be a clue to uncovering how these animals “see” the Earth’s magnetic field.

Sounds good

Hearing, like the sense of touch, involves detecting the movement of molecules in the world outside ourselves. Those outside vibrations become internal signals, which can combine into conversations or orchestrations.

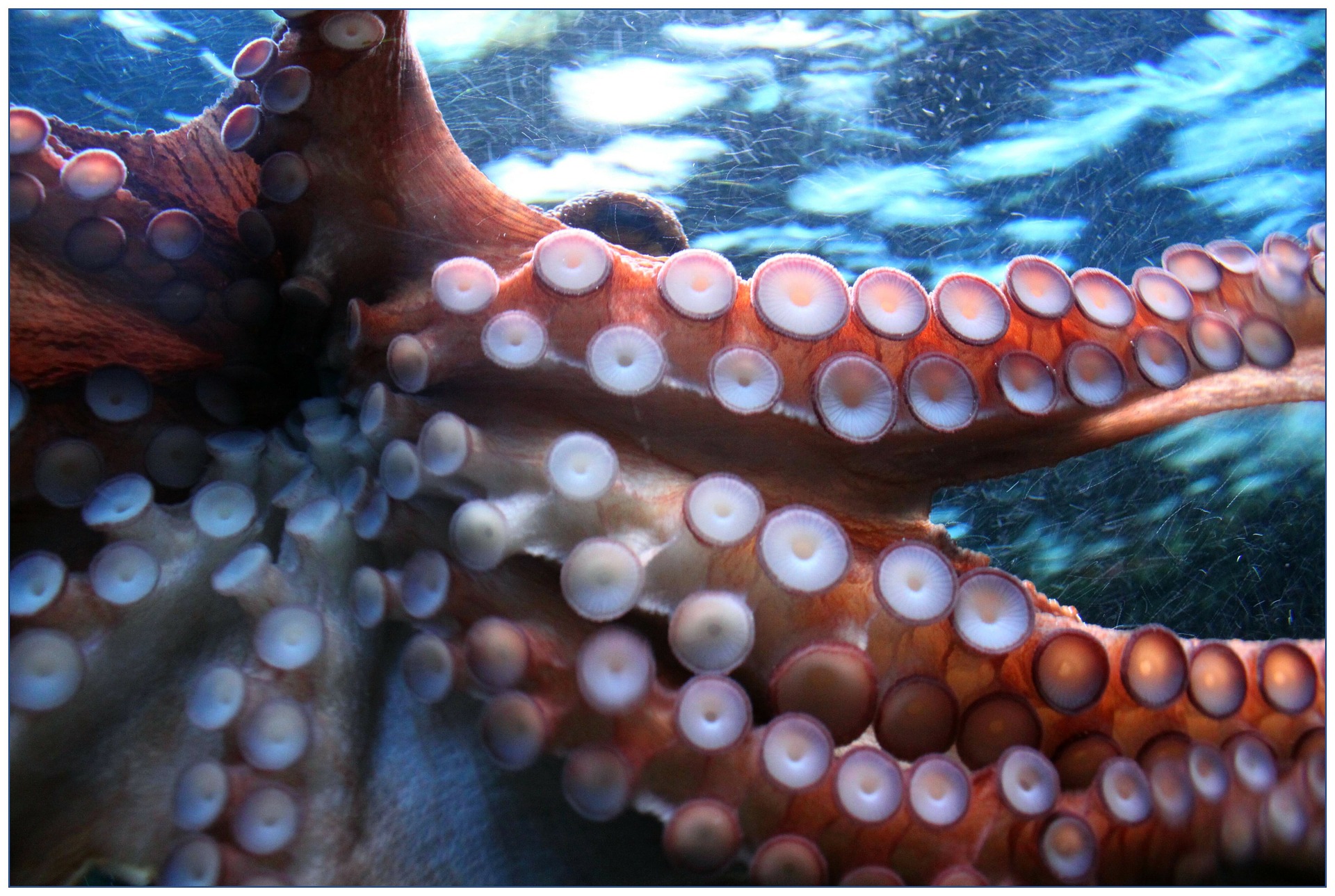

Octopus senses

Harvard scientists have identified a novel family of sensors in the first layer of cells inside the suction cups of octopus tentacles that have adapted to react and detect molecules that don’t dissolve well in water, which may help them figure out what it’s touching and whether that object is prey.

Smell-O-Vision

Odors take a direct route to the limbic system which is involved with emotion and memory, which is why often the nose knows before our other senses can catch up.

The science of sniffing

Learn how scent, emotion, and memory are intertwined.

Exploring the osmocosm

Harold McGee, author of “Nose Dive: A Field Guide to the World’s Smells,” discusses the “osmocosm,” the vast universe of scents that waft from our feet, a field of flowers, and even space itself.

Love stinks

Feeling attracted to someone? It turns out your eyes aren’t the only sensory organ involved.

Sniffing out smells

A study by neurobiologists at Harvard Medical School provides insights into the mystery of scent and its connection with the brain.

Narwhal senses

Harvard School of Dental Medicine researchers found nerves, tissues, and genes in the narwhal tusk pulp that are known for sensory function and that help connect the tusk to the brain, adding to the ways in which the narwhal uses its tusk.

Tasty treats

The sense of taste is built into our genes, unlike recognizing smells which is learned. The receptors for sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami are at work even in newborns.

How does flavor work?

During the Harvard Horizons talks and on the “Veritalk” podcast, Harvard alum Jess Kanwal explains that our brain’s ability to combine taste and smell is just one example of how we are able to mix and match senses—with very interesting results.

Where do you lie on the taste spectrum?

Research shows that about 25% of the population is extremely sensitive to bitter tastes, and about the same percentage can barely notice them.

What to talk about when you talk about tastes

Instead of looking for hints of melon, experts say it’s better to move away from the established lexicon and find your own words for the things you’re tasting.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE