As delivered.

It is hard to find words to convey how honored and grateful I am to receive the Kluge Prize and how humbled I feel to be included in the pantheon of its recipients. I am delighted to be awarded this recognition by the Library of Congress, an institution that has meant so much to me throughout my scholarly career. From the papers of 19th century South Carolina Congressman and Senator James Henry Hammond, a key figure in my first two books, to the diaries and letters of Clara Barton and the searing Mathew Brady photographs so central to my last, the Library’s collections have been essential to my explorations of the American South and the nation’s experience of Civil War.

That this award comes from the Library of Congress is a signal honor. That it is awarded for achievement in the “study of humanity” is a recognition I could scarcely have dreamed of. It affirms what I have seen as a vocation, a calling, a life purpose—both in my own dedication to such study, but also in my efforts on behalf of the institutions, especially universities, that have enabled and encouraged this pursuit.

The path I have chosen into the study of humanity has been history. From my earliest years growing up in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley in the 1950s and 60s, I felt the presence of the past all around me. I lived on a farm on the Lee-Jackson highway, amidst fields where Confederates and Yankees had skirmished, and played Civil War with my brothers in the woods near our house. But I also knew, even as a young child, that my own era was a historic time in its own right, one of controversy and of challenge to the entrenched order of segregation that had replaced slavery after the Civil War. History seemed to surround me even as a new history was being created before my eyes.

The past of slavery, war, and racial injustice so present in my childhood would later become the focus of my scholarly work. But the questions I would ask of the 19th century had implications for my own world as well. I sought through research and writing to understand how human beings had come to create the slave society of the Old South, and how slavery’s oppressions had become for millions of white southerners not just an accepted way of life, but what they justified as a “positive good” and what they ultimately, in the hundreds of thousands, died to defend. A century later, I had grown up amongst adults who supported segregation, a system that had seemed to me even as a young child at odds with the democratic and Christian values those same adults taught me to espouse. If I could understand the southern past, perhaps I could better comprehend the southern present.

My PhD dissertation and first book were about the proslavery argument. You might say I wanted to understand inhumanity—how men and women throughout history have persuaded themselves to defend ideas, practices, societies, governments that we of a different era see as indefensible. I wanted to know how humans can become blind to evil. Perhaps if we could understand their processes of denial and rationalization we might gain insight into our own failures of vision, the shortcomings of our own time.

History, in other words, can expand our awareness of ourselves. It releases us from the confines of our own individual lives; it offers us other ways of seeing that cast our assumptions into relief. It reminds us of choices people have made—or not made—and thus illuminates realms of possibility. It shows us that things have been otherwise and reminds us they can be different once again. By documenting contingency and agency, history undermines any acceptance of crippling inevitability. And contingency means opportunity. It means that we can change things and that what we do matters. To my mind this may be history’s most important lesson.

Although I at first focused my attention on the society and culture of the old South, the implications of the questions I was exploring in my writing and teaching led me inexorably toward the Civil War. It seemed I had been steeped in that war from my earliest days. As I began my deeper scholarly explorations into its history, I soon came to understand Ernest Hemingway’s observation to F. Scott Fitzgerald. “War,” he said, “is the best subject.” For me it proved irresistible to study humanity when it is under maximum pressure, when decisions and choices are literally matters of life and death, when the possibility for the best of humanity—courage, sacrifice—and the worst of humanity—cruelty, brutality—collide.

And I found myself drawn to explore with my students other wars as well—Vietnam, the two World Wars—What was different and what unchanging about the human response to combat and conflagration? What was the product of time and circumstance and what the result of an essential and enduring humanity? How did the inhumanity of war compel its participants to reaffirm and reassert what humanity truly meant? How did war extend beyond the battlefield to engulf the lives of civilians, of women and of children? What, as we might put it, is the human face of war?

It was in war’s foregrounding of death that I encountered an unparalleled line of sight into the human condition and the subject for my most recent book. Mortality is a defining feature of humanity, and our recognition and anticipation of our inevitable end is a key element differentiating us from animals. All of life—and all of philosophy—Montaigne observed—is about learning to die. Yet we do so in different ways in different eras and different places. Facing the unprecedented slaughter of Civil War—more than 2 percent of the population died in the course of the war—the equivalent of about 7 million people today—Americans confronted death in a manner both old and new. The widely shared Christian ideology of the Good Death provided lessons in how to die that shaped the response to unimaginable and unfathomable industrialized slaughter. The insistence of our forbears on adapting the rituals and practices that preserved their humanity even in the face of catastrophe seemed to me an affirmation of the power and resilience of the human spirit. Even in almost impossible circumstances, soldiers and civilians alike struggled to bury, name and honor the dead in ways that affirmed the value of each human life. The national cemetery system that emerged from the war represents the expression of this impulse on a national level. For me, the research and writing for this book served as an excursion into the past with powerful resonance for a future that awaits us all. I have been deeply moved and gratified to learn that readers ranging from hospice workers to clergy, to active and veteran military have found that this book has spoken to them and to their experience.

That is just a brief glimpse into what the study of humanity—and inhumanity—has meant for me and into the kinds of questions that collections like the ones here at the Library of Congress have enabled me to ask.

Other institutions have of course also supported this work, which would never have been accomplished without the rich intellectual environment of teaching and research nurtured by American higher education. Universities have served as the locus for humanistic inquiry from the time of their founding in the 11th century; society has assigned primary responsibility for this stewardship to them. It has been the unique role of the university both to serve the immediate and urgent present and at the same time to look beyond it to pose larger questions of meaning—not just to propel us towards our goals but to ask what those goals should be, to understand who we are, where we came from, where we are going and why.

Yet we find ourselves in a time when the value and legitimacy of these questions—and of the fields that embody them—are being criticized, weakened, marginalized. Increasingly, education is seen as instrumental. We expect it to provide a direct path to a specific job. We fail to ask how it will produce a thoughtful citizen or a person who can imagine beyond the moment in which we find ourselves to see and build the changing world ahead, or a leader who can begin to address the profound impact of our extraordinary technological advances on our culture, our society and our very understanding of what it is to be human. We see results of this neglect all around us. We have invented the marvels of social media, but not figured out the ethics of the profound challenges its poses. We have made torrents of information available to almost everyone but not equipped them with the skills of analysis and habits of discernment to separate truth from falsehood—or perhaps most alarmingly, to believe that this distinction matters. We are a society enthralled by the notion of innovation. But how can we imagine a new future without grasping how things were once different and can be different again?

We are witnessing sharp declines in the fields designed to ask such questions and nurture such skills. I speak, of course, of the humanities and what are known as the “qualitative”—non mathematical—social sciences . Languages, literatures, history, philosophy, religion, anthropology, parts of sociology and political science are at the core of the endeavor, and their departments, majors, jobs and enrollments are plummeting. At Penn State, for example, the five years from 2010 to 2015 saw a 40% decline in humanities majors. At the University of Illinois at Champaign Urbana there were 414 English majors in 2005 and 155 in 2015. Nationwide, numbers of history majors are down 45% since 2007. Since the 1990s, English majors have declined by half. The University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point announced it would abolish 13 departments, including French, German, Spanish, Philosophy and political science. One state governor listed the specific fields to be favored with state support, explicitly tying educational resources to job outcomes. “I want to spend our dollars giving people sciences, technology, engineering, math degrees…. So when they get out of school they can get a job.” He observed that his state didn’t need any more anthropologists.

In fact, humanists do get jobs and over a lifetime earn only slightly less than their peers in social and natural sciences. Jobs are, of course, important. But they are not enough to serve as the exclusive purpose of higher education. When we define the role of learning as solely to drive economic development, we risk losing sight of the broader and deeper questions, of the kinds of inquiry that enable the critical insight, that build the humane perspective, that foster the restless skepticism and unbounded curiosity from which our profoundest understandings so often emerge. We should not forget Einstein’s words: “Not everything that counts can be counted; and not everything that can be counted counts.”

It seems to me telling that one set of higher education institutions has not shared in this recent decline in the importance of the humanities. These are our military academies. Take the example of West Point. From its origins as an engineering school, the United States Military Academy has evolved over two centuries to be a very special sort of liberal arts college, one that recognizes that many of the most significant lessons for the leadership it must foster emerge from the study of humanity. The Academy describes it this way: “the expansion of a person’s capacity to know oneself and to view the world through multiple lenses.” The distinguished Academy graduate General George Patton—whose papers are here at the Library of Congress—insisted that a successful soldier must know history. “To win battles,” he observed, “you do not beat weapons—you beat the soul of man.” Alexander the Great slept with two things under his pillow: a dagger and a copy of Homer’s Iliad.

To understand the human soul. No small aspiration. But one that has propelled my work for decades and the work of the humanities for millennia. In identifying what is distinctively human, we necessarily commit ourselves to its preservation and enhancement, to the appreciation of what unites us rather than the distraction of what divides us, to the advancement of the humane in a world that often seems bent on destroying it. We must support universities in their dedication to these efforts. And we must adopt a discourse that honors rather than disparaging these fields of inquiry.

But to make this possible and sustainable within universities, we must also build broader understanding of the importance of the study of humanity outside and beyond them. And so let me return to where I began, to where we find ourselves tonight. In serving as the Library of Congress, this institution also must serve all the people that Congress represents—not just scholars but the curious citizens of an entire nation. All of us are in this room because we are in some way connected to that work. Because we are somehow invested in that endeavor. The extraordinary advances of science and technology that lie before us must be shaped by human and humane purposes if those values and perhaps even human kind are not to be destroyed. Let me invoke the historian’s sense of contingency that I earlier described: it is up to us to define the nature and quality of human possibility. The contents of this Library can help inspire us to inspire others to understand what those possibilities can be.

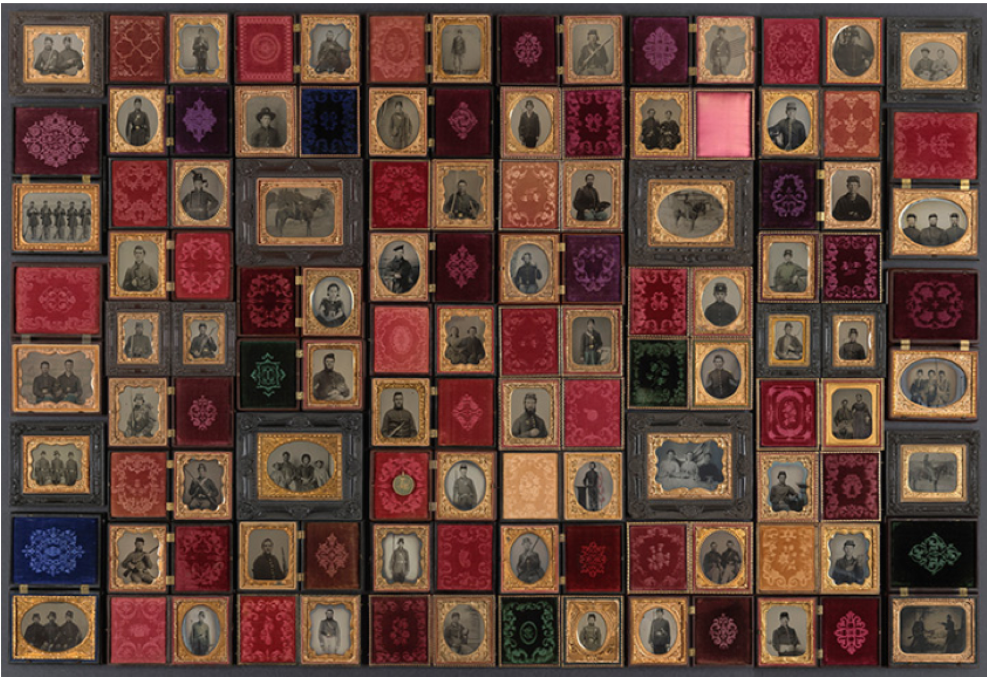

Let me make this point by closing with a treasure from the Library. I spoke earlier of the face of war. The Library of Congress possesses a remarkable collection of more than 2000 Civil War faces which has been assembled and donated by Tom Liljenquist and his three young sons. Inspired by newspaper photographs of US servicemen and women killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Liljenquists regard their collection of tintypes and ambrotypes as a memorial to the soldiers of the Civil War.

Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters. Ambrotype by unidentified photographer, between 1863 and 1865. Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Part of the Last Full Measure Exhibition, Library of Congress.

Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters. Ambrotype by unidentified photographer, between 1863 and 1865. Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Part of the Last Full Measure Exhibition, Library of Congress.

Here is one of the ambrotypes from the collection. It has been tentatively identified as Sergeant Samuel Smith, his wife Mollie and daughters Mary and Maggie. The image was found in Cecil County Maryland, so it is likely that this soldier was in one of 7 regiments of United States Colored Troops raised in that state.

Like all of the portraits in this collection, it speaks eloquently to us across the century and a half that separates us. For this soldier and his family, the message is one of pride, an affirmation of the new freedoms war had enabled him to claim. Slavery would have denied him the right to legally marry or to protect his wife and children from sale. This portrait is of a free man; it proclaims a new day for black families, a new respectability of fine clothing and of daughters in matching coats and bonnets. And it portrays a soldier, an African American who under slavery would have been prohibited from bearing arms and until 1863 could not have enlisted in the army. Now he has joined what would be nearly 200,000 other black Americans to fight for freedom, to risk enslavement if captured and to establish a claim to full citizenship and humanity as the republic’s bold defenders. In this photograph, Sergeant Smith—or whoever this might be—makes a statement about a new order of things. It is his own declaration of independence, his personal affirmation that all men—that he—has been created equal that he is fighting for a new birth of freedom.

Union Case Four of the Last Full Measure Exhibition, Library of Congress.

Union Case Four of the Last Full Measure Exhibition, Library of Congress.

But these 2000 portraits and the thousands more like them are intended to send us another message as well, one that speaks directly to the meaning of the study of humanity across time and space. These soldiers staring into the photographer’s lens are self-consciously reaching through history. They are documenting their faces and their uniforms partly because they know they may be killed in the battles ahead. But they also know they are making history in this war, and they want to capture it for us. Attention must be paid, they are saying. Don’t forget who we were and what we did. Let us give you the means to see us, to understand us long after we are gone.

The present is delivered to us at a price paid by those who came before. History helps us remember our accountability to them as well as our obligations to more than just ourselves and more than just our own time. It is a way of knowing and of valuing that has never mattered more.