History of the Presidency

Term of office: 2024-present

Alan M. Garber

Alan Garber became president of Harvard University on August 2, 2024.

2000s

Term of office: 2023-2024

Claudine Gay became the 30th president of Harvard University on July 1, 2023.

Prior to becoming president, she spent five years leading Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences as the Edgerley Family Dean, having served previously as dean of social science from 2015 to 2018. Gay was recruited to Harvard in 2006 as a professor of government. She was also appointed as a professor of African and African American Studies in 2007. She was named the Wilbur A. Cowett Professor of Government in 2015.

As FAS dean, Gay guided efforts to expand student access and opportunity, spur excellence and innovation in teaching and research, enhance aspects of the FAS’s academic culture, and bring new emphasis and energy to areas such as quantum science and engineering; climate change; ethnicity, indigeneity, and migration; and the humanities. She successfully led the FAS through the COVID pandemic, consistently and effectively prioritizing the dual goals of safeguarding community health and sustaining academic continuity and progress. She also launched and led an ambitious, inclusive, and faculty-driven strategic planning process, intended to take a fresh look at fundamental aspects of the FAS’s academic structures, resources, and operations and to advance academic excellence.

Gay is a leading scholar of political behavior, considering issues of race and politics in America. She has explored such topics as how the election of minority officeholders affects citizens’ perceptions of their government and their interest in politics and public affairs; how neighborhood environments shape racial and political attitudes among Black Americans; the roots of competition and cooperation between minority groups, with a particular focus on relations between Black Americans and Latinos; and the consequences of housing mobility programs for political participation among poor people. Gay is a dedicated educator and mentor whose courses have focused on such topics as racial and ethnic politics in the U.S., Black politics in the post-Civil Rights era, American political behavior, and democratic citizenship. She is founding chair of the Inequality in America Initiative, a multidisciplinary effort launched in 2017.

Prior to joining the Harvard faculty, Gay was an assistant professor of political science at Stanford University from 2000 to 2005, and an associate professor (tenured) from 2005 to 2006. She earned a B.A. in economics from Stanford University, where she received the Anna Laura Myers Prize for best senior thesis in the department. She earned her Ph.D. at Harvard in 1998, receiving the Toppan Prize for best dissertation in political science.

A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Gay has pursued her scholarship as a fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard. She currently serves on the boards of the Pew Research Center, Phillips Exeter Academy, and the American Academy of Political and Social Science. She also served as a member of the American Association of Universities advisory board on racial equity in higher education.

Term of office: 2018-2023

Lawrence S. Bacow is President Emeritus and Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. Bacow served as the 29th president of Harvard University. Widely recognized as one of higher education’s most respected leaders, Bacow’s tenure at Harvard was marked by the creation of a range of academic initiatives, advocacy for public service, diversity and access to opportunity, and steady leadership of the university through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since taking office in 2018, Bacow marshaled academic and financial resources to advance the university’s teaching and research mission, creating new interdisciplinary collaborations on issues such as climate change, inequality, global health, the future of cities, as well as new initiatives in science and technology. The Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery initiative, the Harvard Quantum Initiative, the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence, the Bloomberg Center for Cities and the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability were all established under Bacow’s tenure. He also expanded the role and operation of Harvard’s office for Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging and created a new vice provost for climate and sustainability and an associate provost role for student affairs.

Bacow stewarded Harvard through the COVID-19 pandemic. At his direction, Harvard became one of the first universities to shift coursework online in March 2020. With the presidents of Stanford and MIT, Bacow called for reduced density and social distancing and related disruption of university operations to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. Harvard avoided pandemic-related layoffs and provided widespread support for employees, including an emergency financial assistance fund and pay and benefit continuity for those whose work had been displaced due to the pandemic. Bacow also advocated for the resumption of essential research activities as early pandemic measures stabilized conditions.

In July 2020, in response to a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement announcement that international students would have to depart the country if attending institutions that shifted to online instruction, Bacow initiated a successful lawsuit to stop the directive, ensuring international students at Harvard and nationwide would be able to continue to study in the United States.

In June 2022, Bacow announced his plans to step down from the Harvard presidency on June 30, 2023. In his message to the Harvard community, he called the opportunity to serve Harvard, “the privilege of a lifetime.”Prior to being elected to the Harvard presidency in 2018, Bacow served as a member of the Harvard Corporation, one of two of the University’s governing boards, for seven years. While on the Corporation he served in a variety of leadership posts, including chairing the finance committee, committee on facilities and capital planning, and the governing boards’ joint committee on inspection. Bacow maintained an active academic portfolio while serving on the Corporation, with a scholarly focus on higher education and leadership. From 2011 to 2014, he served as President-in-Residence in the Higher Education Program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. From 2014 to 2018, he served as the Hauser Leader-in-Residence at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government’s Center for Public Leadership. He has devoted his time to advising many new and aspiring higher education leaders, mentoring students interested in careers in education, teaching in executive education programs, and writing and speaking on salient topics in higher education – innovations in learning, academic freedom, the economics of universities, the impact of digital technologies, and university governance and leadership, among others.

Prior to joining Harvard, Bacow was President of Tufts University from 2001 to 2011. During his tenure, he advanced the university’s commitment to excellence in teaching, research, and public service and fostered collaboration across the university’s eight schools. Under his leadership, Tufts pursued initiatives to enhance the undergraduate experience, deepen graduate and professional education and research in critical fields, broaden international engagement, and promote active citizenship among members of the university community.

While at Tufts, Bacow emerged as a nationally recognized champion of expanding access to higher education through need-based student aid, while also advocating vigorously for federal support of university-based research. He worked to engender novel connections across academic disciplines and among Tufts’ wide array of schools and helped craft a new partnership between the university and its principal teaching hospital, Tufts Medical Center. Bacow convened an international conference of higher education leaders in 2005 to initiate the Talloires Network, a global association of colleges and universities committed to strengthening the civic roles and social responsibilities of higher education. He launched Tufts’ Office of Institutional Diversity and highlighted inclusion as a cornerstone of the university’s excellence. He also strengthened relations between Tufts and its host communities and expanded outreach to alumni, parents, and friends.

While guiding Tufts through the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and its aftermath, he brought to fruition the most ambitious fundraising campaign in the university’s history. While president of Tufts, Bacow served as chair of the council of presidents of the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, chair of the executive committee of the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in Massachusetts, and a member of the executive committee of the American Council of Education’s board of directors.

During his tenure at Harvard, he has served on the Boards of the Association of American Universities, the American Council of Education, and the Consortium on Advancing Higher Education. Before his time at Tufts, Bacow spent 24 years on the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he held the Lee and Geraldine Martin Professorship of Environmental Studies. He served as the elected Chair of the Faculty (1995-97) and then as Chancellor (1998-2001), one of the institute’s most senior academic officers. As Chancellor, he guided the institute’s efforts in undergraduate education, graduate education, research initiatives, international and industrial partnerships, and strategic planning, while playing an integral role in reviewing faculty appointments and promotions across MIT.

Early in his career, Bacow held visiting professorships at universities in Israel, Italy, Chile, and the Netherlands. As a member of the faculty, his academic interests ranged across environmental policy, bargaining and negotiation, economics, law, and public policy. He emerged as a widely recognized expert on non-adjudicatory approaches to the resolution of environmental disputes. Bacow was co-director of MIT’s Consortium on Global Environmental Challenges and played a key role in launching and leading both the MIT Center for Environmental Initiatives and the MIT Center for Real Estate. He was also associated with the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. He is the author or co-author of four books and numerous scholarly articles on topics related to environmental policy, economics, land use law, negotiation, and occupational health and safety. Bacow formerly served as senior advisor to Ithaka S+R, a nonprofit organization devoted to innovation in higher education, and was one of the authors of its major 2012 study of online learning systems in U.S. higher education. He served as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Lincoln Project on preserving and strengthening the nation’s public research universities (2014-16), as well as on the White House Board of Advisors on Historically Black Colleges and Universities (2010-15). In 2017, he was Clark Kerr Lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley and the Robert Atwell Lecturer in 2003 at the American Council of Education. A Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he has received seven honorary degrees.

Bacow was raised in Pontiac, Michigan. Interested in math and science from an early age, he attended college at MIT, where he received his S.B. in economics in three years and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa. He went on to earn three degrees from Harvard: a J.D. from Harvard Law School, an M.P.P. from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, and a Ph.D. in public policy from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. He is married to Adele Fleet Bacow, a pioneering urban planner who he met on his first day of orientation at Harvard Law School. Adele is widely known nationally for her work in urban planning, cultural economic development, and the arts, and was recognized by Tufts in 2012 with the Hosea Ballou Medal, an honor bestowed only 17 times since 1939 for exceptional service to the university. The Bacows have two sons and four grandchildren. Bacow is an avid runner, sailor, and skier. He launched the President’s Marathon Challenge at Tufts to raise funds in support of health and nutrition research, and he has completed five marathons. He was a member of the varsity sailing team at MIT, and the Sailing Pavilion at Tufts is named for him and his wife.

Term of office: 2007-2018

Drew Gilpin Faust is President Emerita and is the Arthur Kingsley Porter University Research Professor.

Faust served as the 28th president of Harvard University from July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2018. She was Harvard’s first female president.

Faust grew up in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and received her B.A. from Bryn Mawr College, magna cum laude and her M.A. and Ph.D from the University of Pennsylvania. She served on the faculties of Penn and Harvard for nearly a half century and was President of Harvard from 2007 to 2018. She is author of seven books, including National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Her most recent book is a memoir, Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury (2023). In 2018 Faust was awarded the John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity.

Term of office: 2001-2006

Lawrence H. Summers is President Emeritus and Charles W. Eliot Professor of Harvard University. He has served in a series of senior public policy positions, including Director of the National Economic Council for the Obama Administration from 2009 to 2011, and Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, from 1999 to 2001. He received his bachelor of science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1975 and a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1982.

In 1983, he became one of the youngest individuals in recent history to be named a tenured member of Harvard’s faculty. In 1987, he became the first social scientist ever to receive the annual Alan T. Waterman Award of the National Science Foundation (NSF), established by Congress to honor an exceptional young U.S. scientist or engineer whose work demonstrates originality and a significant impact within one’s field. In 1993, Mr. Summers was awarded the John Bates Clark Medal, given every two years to the outstanding American economist under the age of 40. Mr. Summers took leave from Harvard in 1991 to return to Washington, this time as vice president of development economics and chief economist of the World Bank.

In 1993, Summers was named as the nation’s Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Affairs. In 1995, then Secretary Robert E. Rubin promoted Mr. Summers to the department’s number-two post, Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, in which he played a central role in a broad array of economic, financial, and tax matters, both international and domestic. On July 2, 1999, the United States Senate confirmed Mr. Summers as Secretary of the Treasury. At the end of his term as Treasury Secretary, Mr. Summers was awarded the Alexander Hamilton Medal, the treasury department’s highest honor.

On July 1, 2001, Mr. Summers took office as the 27th president of Harvard University. As president he oversaw significant growth in the faculties, the further internationalization of the Harvard experience, expanded efforts in and enhanced commitment to the sciences, laying the ground work for Harvard’s future development of an expanded campus in Allston, and improved efforts to attract the strongest students, regardless of financial circumstance, with the Harvard Financial Aid Initiative. These initiatives were sustained by five years of successful fundraising and strong endowment returns.

In 2009, Mr. Summers was appointed to serve as the Director of the National Economic Council for the Obama Administration. He returned to his position at Harvard in early 2011. As Director of the White House National Economic Council and Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, Summers served as a key economic decision-maker in the Obama administration. Mr. Summers was the chief White House advisor to the President on the development and implementation of economic policy and led the President’s daily economic briefing. He was also a frequent public spokesman for the Administration’s policies.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, on November 30, 1954, Mr. Summers spent most of his childhood in Penn Valley, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia, and was educated in the Lower Merion public schools. He and his wife Elisa New, a professor of English at Harvard, reside in Brookline with their six children.

What’s in a name?

Lowell House

Named for Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell and his family, the Lowell House, constructed in 1930, is home to a collection of 17 Russian bells, which were given as a gift in 1930.

1900s

Term of office: 1991-2001

Neil L. Rudenstine (1935-) served as Harvard’s president from 1991-2001. Rudenstine, a scholar of Renaissance literature, received his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1964. After serving as a faculty member at Harvard for four years, he joined the faculty at Princeton, where he had earned his undergraduate degree.

At Princeton, Rudenstine held a number of posts in academic administration, including dean of students, dean of the college, and provost.

Rudenstine then served as executive vice president of the Mellon Foundation for four years before being chosen for the Harvard presidency in 1991.

At Harvard, as part of an overall effort to achieve greater coordination among the University’s schools and faculties, Rudenstine set in motion an intensive process of University-wide academic planning intended to identify some of Harvard’s main intellectual and programmatic priorities.

In 1999, he announced the launch of a major new venture in interdisciplinary learning, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, created through the merger of Radcliffe College with Harvard.

During his tenure Rudenstine worked to sustain and build federal support for university-based research. Under his leadership, Harvard’s federally sponsored research grew to $320 million in 2000, up from $200 million in 1991.

Rudenstine also stressed the University’s commitment to excellence in undergraduate education, the importance of keeping Harvard’s doors open to students from across the economic spectrum, the task of adapting the research university to an era of rapid information growth, and the challenge of living together in a diverse community committed to freedom of expression.

Rudenstine led Harvard’s first University-wide funding campaign in modern times and what was then the largest higher education campaign in history. The efforts surpassed the goal of $2.1 billion to raise more than $2.6 billion from about 175,000 alumni and friends of Harvard.

That success allowed the University to take meaningful steps toward its goals, such as increasing both undergraduate and graduate student financial aid, embarking on new construction projects to provide cutting-edge facilities for study and research, and endowing new chairs and professorships to ensure that Harvard would continue to attract top faculty.

Since stepping down from the presidency, Rudenstine has been involved in a digital arts venture, ArtSTOR, and taught courses at Princeton.

Rudenstine is married to art historian Angelica Zander Rudenstine.

The Neil L. and Angelica Zander Rudenstine Gallery at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research is the only exhibition space at Harvard devoted to works by and about people of African descent.

Terms of office: 1971-1991 and 2006-2007

Derek Bok served as interim president of Harvard University from July 1, 2006, to June 30, 2007. Bok was the only person in the modern era to twice serve as Harvard president. As interim president, Bok devoted himself to bringing to a successful conclusion an ongoing review of undergraduate education, planning for the development of University land in Allston, and identifying organizational changes necessary to promote interdisciplinary research, such as reform of the academic calendar. Bok’s annual report outlines the work that went into advancing these goals.

Bok, the 300th Anniversary University Research Professor and faculty chair of the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations, previously served as the 25th president of Harvard from 1971 to 1991. Prior to being named president, Bok served as dean of Harvard Law School from 1968 to 1971.

During his 20-year tenure as president, Bok restructured the University’s central administration and oversaw creation of a Core Curriculum that became the framework for undergraduate education at Harvard. He advocated increasing the number of female undergraduates, supporting the 1975 adoption of equal-access and gender-blind financial-aid policies in admissions.

Bok also focused on expanding the Kennedy School of Government faculty and programs. He encouraged the establishment of academic programs and research centers addressing issues such as AIDS, energy and the environment, poverty, professional ethics, smoking, and international security.

As president, he was a vocal advocate for student participation in public-service programs. By the end of his presidency, more than 60 percent of Harvard undergraduates were engaged in some form of public service. Envisioning the important role Harvard could play internationally, Bok also signed innovative debt-for-scholarship agreements with the governments of Ecuador and Mexico during his tenure.

In 1975, Bok established the Office for the Arts, whose programs to this day serve more than 3,000 undergraduates annually. He established the Danforth Center for Teaching and Learning to explore innovations in undergraduate teaching, which was renamed the Bok Center in 1991.

He has written six books on higher education: Our Underachieving Colleges (2005), Universities in the Marketplace (2003), The Shape of the River (1998, with William G. Bowen), Universities and the Future of America (1990), Higher Learning (1986), and Beyond the Ivory Tower (1982).

In addition to studying the state of higher education, Bok is also the author of two books examining the adequacy of the U.S. government in coping with the nation’s domestic problems: The State of the Nation (1997) and The Trouble with Government (2001).

He serves as chair of the board of the Spencer Foundation.

Bok has an A.B. from Stanford University, a J.D. from Harvard Law School, and an A.M. in economics from George Washington University. Following law school, he was named a Fulbright Scholar and studied at the University of Paris’s Institute of Political Science.

Bok is married to Sissela Myrdal Bok, a writer and philosopher who is senior visiting fellow at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies. They have two daughters and one son.

Term of office: 1953-1971

Arriving in Massachusetts Hall after presiding over Lawrence College, Nathan Marsh Pusey (1907-2001) was the second Harvard president to bring previous presidential experience with him. For Pusey, that meant tangles with the infamous Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy (R-Wis.).

The new president had hardly been confirmed by the Board of Overseers in June when McCarthy took aim at him in a published letter. “When McCarthy’s remarks about me are translated, they mean only I didn’t vote for him,” Pusey wryly replied. The incident made national news, the vast majority of it against McCarthy. In November, after Pusey had spent little more than two months in office, McCarthy attacked Harvard. Pusey parried with the unflappable style that had earlier served so well.

Pusey’s firmness of principle reflected his deeply religious nature, and The Memorial Church and the Divinity School benefited from his continuing efforts to enhance Harvard’s spiritual fortunes. Nonetheless, Pusey was also one of Harvard’s great builders, resuming a scale of new construction to rival that of the Lowell administration.

In 1957, Pusey announced the start of A Program for Harvard College, an $82.5 million effort that actually raised $20 million more and resulted in three additions to the undergraduate House system: Quincy House (1959), Leverett Towers (1960), and Mather House (1970). During the 1960s, the Program for Harvard Medicine raised $58 million. In April 1965, the Harvard endowment exceeded $1 billion for the first time. By 1967, Pusey found himself making the case for yet another major fundraising effort seeking some $160 million for various needs around the University.

Other major structures of the Pusey era include the University Herbaria building (ca. 1954), the Loeb Music Library (1956), Conant Chemistry Laboratory (1959), the Loeb Drama Center (1960), the Center for the Study of World Religions (1960), the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (1963), Peabody Terrace (1964), William James Hall (1965), Larsen Hall (1965), the Countway Library of Medicine (1965), and Holyoke Center (1966). A 1960 bequest from art connoisseur Bernard Berenson, Class of 1887, allowed Villa I Tatti (Berenson’s great and storied estate near Florence, Italy) to become a special Harvard treasure as the home of the Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. Fundraising for structures such as Pusey Library and the undergraduate Science Center began toward the end of Pusey’s term.

Pusey became one of Harvard’s most widely traveled chief executives, chalking up official trips to Europe (England, France, Scotland, Switzerland; 1955), East Asia (Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan; 1961), and Australia and New Zealand (1968).

Toward the end of his term, Pusey found himself once again beset by controversy – this time, from within. Fueled by burning issues such as the Vietnam War, civil rights, economic justice, and the women’s movement, student activism escalated to the boiling point by the late 1960s at Harvard and elsewhere. On April 9, 1969, radical students ejected administrators from University Hall and occupied the building to protest Harvard’s ROTC program and University expansion into Cambridge and Boston neighborhoods. Early the next morning, many protesters sustained injuries requiring medical treatment after Pusey called in outside police to remove the demonstrators. In response, other students voted to strike and boycott classes. The University almost closed early. The gateway had just opened onto the greatest period of sustained upheaval in Harvard history.

Pusey defended his actions until the end of his long life, but the events of April 1969 undoubtedly shortened his presidency. In February 1970, he made a surprise announcement: he was retiring two years early. Pusey left Harvard in June 1971 to become the second president of New York’s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Term of office: 1933-1953

Mindful of the upcoming Tercentenary Celebration in 1936, James Bryant Conant (1893-1978) opted for a minimal installation ceremony in the Faculty Room of University Hall on Oct. 9, 1933. There was little else minimal about him. Conant operated on a grand scale like Lowell’s but saw his proper task as populating Lowell’s vastly expanded physical plant with talented students and scholars.

Toward this end, at his very first Harvard Corporation meeting (Sept. 1933), Conant proposed an effort later known as the 300th Anniversary Fund. Within two years, it supported the creation of (1) the special academic position of University Professor, which gives exceptional scholars the run of the University to foster cross-disciplinary research on the frontiers of knowledge, and (2) National Scholarships for highly promising students, regardless of financial means. By seeking out and assisting students who might not otherwise attend college, the National Scholarships enhanced undergraduate diversity.

Through issues surrounding the selection of National Scholarship recipients, Conant became deeply involved in the expanded use of the Scholastic Aptitude Test developed by Princeton’s Carl Campbell Brigham. Conant eventually headed the commission whose recommendations led to the formation of the Educational Testing Service in 1947.

Immersion in such major public questions typified the man. Conant testified before U.S. Senate committees (e.g., on federal aid to education, creation of the National Science Foundation, and the Lend-Lease Bill). He conferred with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and served as a defense-research emissary to England. In July 1944, Conant offered the facilities of Harvard’s Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (Washington, D.C.) for a U.S. State Department conference on postwar security. The resulting Dumbarton Oaks Proposals laid the foundations of the United Nations Charter.

Conant’s most remarkable governmental role began in 1941 with an appointment to chair the National Defense Research Committee and, later, to serve as special deputy to Vannevar Bush, head of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. As a result, Conant was among the first to receive word of Enrico Fermi’s success in generating the world’s first controlled nuclear chain reaction – a critical step toward the atomic bomb. In July 1945 at Alamogordo, N.M., Conant witnessed the first atomic-bomb test. Shortly after World War II, he traveled to Moscow for talks (involving Great Britain, the U.S., and the Soviet Union) on international control of the bomb.

In the midst of the war, Conant and Provost Paul H. Buck launched a review of the undergraduate curriculum that produced the General Education Program, a reform that shaped Harvard undergraduate studies for more than three decades to come. Published in 1945 as “General Education in a Free Society” (a.k.a. the “Red Book”), the program profoundly influenced high school and college curricula nationwide.

Wartime brought another major change to Harvard classrooms: in summer 1943, Radcliffe women (previously taught in separate, duplicated classes) for the first time attended classes with Harvard men. The “temporary” measure soon became permanent. In 1949, Lamont Library opened as the nation’s first library expressly designed for undergraduates. Seven years earlier, the Houghton Library (for rare books and manuscripts) had opened as the world’s first library with built-in climate control.

The Conant years also saw the birth of major new Harvard subdivisions such as the Graduate School of Public Administration (1935; now the John F. Kennedy School of Government), the Graduate School of Design (1936), and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism (1937). In 1939, the President’s Office moved from University Hall to its current location in Massachusetts Hall.

National duty tapped on Conant’s shoulder once again in 1953: President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Conant to serve as the U.S. high commissioner for Germany, a job that required him to leave Harvard. On Sept. 1, Conant became president emeritus.

Term of office: 1909-1933

For sheer grandeur, no other Harvard presidential installation approaches that of A. Lawrence Lowell (1856-1943). The two days of festivities (Oct. 6-7, 1909) drew some 13,000 spectators, and Harvard conferred 30 honorary degrees.

Born to the prominent Boston family that produced astronomer Percival Lowell (his brother) and poet Amy Lowell (his sister), A. Lawrence Lowell was a man of high scholarship, high standards, and aristocratic bearing who believed in education for all who had the heart and mind to pursue it. Thus, he wasted no time in establishing the Harvard Extension School (1909) as an open-enrollment evening program for the Greater Boston community.

Lowell inherited a College afflicted by a divisive, clubby social outlook that he detested. His inaugural address made clear his desire to restore the “collegiate way of living” that had inspired Harvard’s founding. His correctives shape undergraduate life to this day.

By requiring freshmen to live in Harvard dormitories, Lowell dealt a death blow to the expensive private “Gold Coast” dorms that had sprung up along Mount Auburn Street since the mid-1870s and limited the commingling of social classes. Between 1914 and 1926, four freshman dormitories rose along the Charles. In 1928 came an unexpected gift (eventually totaling $13 million) from Yale alumnus Edward S. Harkness that allowed Lowell to realize one of his deepest dreams: the creation of residential Houses (some subsuming the four recent freshman halls) to replicate the diversity of the larger College, with sophomores, juniors, and seniors living, dining, studying, and socializing with affiliated tutors and faculty. By 1930 and 1931, the first seven undergraduate Houses (Adams, Dunster, Eliot, Kirkland, Leverett, Lowell, and Winthrop) were opening their doors, and the House Plan – one of Harvard’s most successful and distinctive features – was under way. In 1931, the College also began housing freshmen in Yard dormitories.

On every hand, Harvard facilities expanded enormously with the completion of the Gibbs Chemistry Laboratory (1913), the Music Building (1914), Widener Library (1914, opened 1915), the Germanic Museum (now the Busch-Reisinger Museum in Otto Hall; 1921), Lehman Hall (1924), Straus Hall (1926), the Business School’s Georgian-style complex (1927), the Fogg Art Museum (1927), Mallinckrodt Laboratory (1928), the Indoor Athletic Building (1930; now the Malkin Athletic Center), Dillon Field House (1931), Wigglesworth Hall (1931), and The Memorial Church (1932). In 1912, Lowell funded the building of a new president’s House at 17 Quincy St. (now Loeb House). Langdell Hall, partly finished in 1907 to house the Law School Library, was finally completed in 1929.

Lowell was equally concerned with undergraduate education. His term brought the first general examinations, fields of concentration (elsewhere known as “majors”), distribution requirements for subjects outside the concentration, and tutorials (individual or small-group instruction with a tutor). Beyond the College, the University gained new schools in Education (1920) and Public Health (1922).

In 1933, Lowell’s last big dream materialized with the founding of the Society of Fellows, which now allows up to 30 exceptionally promising young scholars (Junior Fellows) to devote three years to full-time scholarship while enjoying regular contact with Senior Fellows in diverse fields.

During World War I when anti-German sentiment ran high, Lowell fiercely defended academic freedom, resisting pressure to fire Psychology Professor Hugo Münsterberg for speaking well of his native Germany. In 1927, Lowell chaired an investigation of the controversial execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. By Lowell’s instructions, investigation documents remained sealed until 1977.

What’s in a name?

Kirkland House

Named for John Thornton Kirkland, who served as President of Harvard from 1810 to 1828, an important period of growth and expansion for the College.

1800s

Term of office: 1869-1909

The presidency of Charles William Eliot (1834-1926) played out on an epic scale like no other, from his record-setting 40 years in office to his transformation of Harvard into a modern research university to his far-reaching impact on U.S. higher education.

In a 105-minute inaugural address (Oct. 19, 1869), Eliot memorably enunciated his grand vision of what Harvard should be. Vigor and longevity made most of it come true. As historian Samuel Eliot Morison explains, Eliot simply “wore down and outlived all his opponents.”

Harvard changed in so many dimensions during the Eliot era that space permits only a sampler of major new arrivals:

- Harvard Summer School (1871)

- Graduate Department (1872; revamped as the Graduate School, 1890; renamed the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 1905)

- Arnold Arboretum (1872)

- Radcliffe College (chartered as the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women [a.k.a. “Harvard Annex”], 1879; chartered as Radcliffe College, 1894)

- Faculty of Arts and Sciences (1890)

- School of Landscape Architecture (ca. 1901; forerunner of the Graduate School of Design)

- Harvard Forest (Petersham, Mass.; 1907)

- School of Business Administration (1908)

At the Medical School in Boston, the curriculum expanded to four years in 1892. Nine years later, a bachelor’s degree became an admissions prerequisite. And in 1906, the new Longwood Avenue quadrangle opened as the largest and most comprehensive medical-school complex in the U.S.

For undergraduates, the Eliot years saw the end of many longstanding requirements such as compulsory chapel (1886), the undergraduate entrance requirement in Greek (1887), and the much-hated “Scale of Merit” (a nitpicking Quincy-era grading system whose last traces disappeared in 1886-87, with the introduction of letter grades).

One of Eliot’s most influential reforms was the development of a system of “spontaneous diversity of choice” in which undergraduates selected most of their own courses. Choice, in turn, stimulated an open-ended curriculum. This elective system constituted a radical break with the time-honored academic practice of specifying a student’s courses according to the year of college. The Harvard experiment soon spread nationwide and changed what it meant to be “educated.” By 1894, Eliot himself had concluded that the new system was “the most generally useful piece of work which this university has ever executed.”

Architecturally, the grandest legacies of the Eliot era are Memorial Hall (1870-78), Sever Hall (1880), Austin Hall (1883), Harvard Stadium (1903), and the Medical School Quadrangle (1906). Matthews (1872), Thayer (1870), and Weld (1872) halls also rose in the Yard; and the Yard’s great gate-and-fence system began to take shape with the completion of the Johnston Gate (1890). Phillips Brooks House opened its doors in 1900 as the home of undergraduate community-service activities.

Having weathered many a storm, Eliot began reaping a harvest of praise around 1894. “One after the other, the greater universities of the country followed the reforms that Harvard had adopted; it was clear by the middle nineties that the Harvard of Eliot [. . .] had set new standards for higher education in America,” writes Morison. “By the turn of the century he was one of the leading public figures of the country; his opinion and support were sought on every variety of public question.”

Few marking Eliot’s silver anniversary could have dreamt that he would serve for another 15 years, retiring as Harvard’s first president emeritus on May 19, the very day of his final confirmation 40 years earlier.

Term of office: 1862-1868

With three years behind him as president of Antioch College, Thomas Hill (1818-1891) was the first Harvard president to bring experience as an academic chief executive to the job. For Hill’s formal installation on March 4, 1863, University Organist and Choirmaster John Knowles Paine composed a new anthem, Domine salvum fac Praesidem nostrum (God Save Our President).

Hill raised admissions standards and took steps toward an elective course system. In 1863, Harvard established public University Lectures by major scholars from Harvard and elsewhere that helped open the way for the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the University Extension program. When faculty positions opened up, Hill scoured the nation for candidates.

Milestones of the period included the first alumni election of Harvard Overseers (Commencement 1866), the beginnings of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (the nation’s first anthropology museum; 1866), and the founding of the Dental School (the nation’s first university dental school; 1867). On July 19, 1865, the governor of Massachusetts presided over the Board of Overseers for the last time, in keeping with a recent legislative act that severed Harvard’s ties to state government.

One student at this time was Robert Todd Lincoln, Class of 1864, son of Abraham and Mary Lincoln. Hoping for parental reinforcement, Hill wrote to the White House on Dec. 9, 1862, to inform the president that the faculty had just approved public admonishment of his son for smoking in Harvard Square after he had privately been warned not to do so.

While Hill never fully realized his vision of Harvard as “an American University in the highest and best sense,” historian Samuel Eliot Morison credits him with moving things in the right direction. Personal factors prevented him from pushing them farther.

To Morison, Hill seemed “too modest, easily balked by difficulty or opposition. With the air and appearance of a kindly, eccentric country minister, he failed lamentably to match the traditional picture of a Harvard president, and shocked Cambridge folk by such lapses from clerical dignity as stripping off his coat to plant ivy against Gore Hall [the library building, 1841-1913]. [. . .]”

On Sept. 30, 1868, Hill resigned, weighed down by “personal bereavements” (Morison). In 1873, he became minister of a church in Portland, Maine, where he happily spent his final years. “Late in life,” notes Morison, “President Eliot declared that he had always been thankful for Hill as a predecessor, since it was he who set the University on the path that she was destined to follow.”

Term of office: 1860-1862 (died in office on Feb. 26)

Two years and ten days after his election to the presidency, Cornelius Conway Felton lay dead. His determination to do the job was too much for a constitution already weakened by a heart condition. (Ironically, he had once presided over a Boston physical-education society.)

Felton (1807-1862) was a noted scholar who also found time to share his talents with the Massachusetts Board of Education and the Smithsonian Institution. Despite its brevity, the Felton presidency produced at least one milestone. At Commencement 1860, Felton conferred degrees upon the first Harvard Class of more than 100 graduates.

More ominously, as civil war loomed on the national horizon, most Southern students left Harvard during the winter break of 1860-61, never to return.

Term of office: 1853-1860

In James Walker (1794-1874), Harvard gained a president whose great words fell short of commensurate deeds. “President Walker’s inaugural address was one of the most solid, sensible, and prophetic orations ever delivered on such an occasion,” notes Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison. “Unfortunately, Dr. Walker was one of those wise persons, not uncommon in academic circles, who cannot get things done. He was too tired or indifferent to advance his own theories effectively.”

Even so, Harvard continued to grow in important new directions. In 1858, two-story Boylston Hall rose to serve the physical sciences (the third story was added in 1871), and the first Appleton Chapel (demolished in 1931) was completed. In the same year, Harvard received $50,000 from Francis Calley Gray that established a Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1859, Abbott Lawrence made his second $50,000 donation to the Lawrence Scientific School. The same year found Harvard’s new Gymnasium (on the site of today’s Cambridge Fire Department Headquarters) under the supervision of professional boxing teacher A. Molyneaux Hewlett, the first Black person to serve on the Harvard staff, who remained until his death in 1871.

Perusing the 1856-57 catalog, students would find Harvard’s first music course (“Vocal Music”). March 1857 brought less harmonious tidings, when the faculty approved the introduction of written final examinations and, of course, bluebooks. With firm faith in old-school classroom recitations as the true measure of mastery, Greek Professor Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles was soon burning bluebooks he had never read.

Troubled by arthritis, Walker submitted his resignation on Oct. 29, 1859, but remained in office until Jan. 26, 1860, a few weeks before the election of his successor.

Term of office: 1849-1853

Jared Sparks (1789-1866) stepped up to the presidency as soon as Edward Everett stepped down on Feb. 1, 1849. Students could not have been more delighted: Sparks had found favor as the first McLean Professor of Ancient and Modern History (1838). But no second golden age was at hand to rival that of President Kirkland.

Even after transferring many onerous tasks to a regent, Sparks did not enjoy his presidential duties. They never left him time enough for historical research. By Oct. 30, 1852, unstable health prompted Sparks to submit a letter of resignation. He agreed to remain until Feb. 10, 1853, when James Walker succeeded him.

The Sparks years, however brief, had their share of surprises. Sparks’s easygoing ways and “distinguished manners” (Samuel Eliot Morison) inspired more students from the South to come to Harvard. At one point, Southerners made up almost a third of the student body.

Over at the Medical School (long by then resettled in Boston), the most famous murder in Harvard history took place on Nov. 23, 1849, when John White Webster killed faculty colleague George Parkman in a dispute over a loan for which Webster provided subsequently compromised collateral. Webster was hanged for the crime on Aug. 30, 1850.

Shortly after taking office, Sparks received a letter from Sarah Pellet, a young woman who wondered whether she might be admitted to the College. On April 25, 1849, Sparks responded, indicating the practical difficulties of having a solitary woman among so many men. But his final remarks held out brighter hopes: “It may be a misfortune, that an enlightened public opinion has not led to the establishment of Colleges of the higher order for the education of females, and the time may come when their claims will be more justly valued, and when a wider intelligence and a more liberal spirit will provide for this deficiency.”

Sparks’ name is now most often invoked because of a single Harvard structure. Instead of moving to Wadsworth House in the Yard, he lived in his own dwelling at 48 Quincy St. The building was moved to 21 Kirkland St. in 1968. Today, Jared Sparks House serves as the residence of the Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church. In 1849, Sparks also moved the President’s Office from Wadsworth House to University Hall, where it remained until 1939.

- Sparks papers at Harvard

- Sparks biography (Morristown National Historical Park)

- How the Liberal Arts Got That Way (New York Times)

- Around the World In 286 Pages: A Dartmouth College drop-out’s ill-fated attempt to walk across the globe (Harvard Crimson)

- Advice to America from a French Friend (Harvard Magazine)

Term of office: 1846-1849

Edward Everett’s arrival opened a 23-year span of five presidencies and one acting presidency in which death and resignation left no one in office much longer than seven years.

With his many years of experience in high-level state, national, and international affairs, Everett (1794-1865) did not relish the prospect of running a university. (Perhaps his experience as a tutor, Overseer, and the first Eliot Professor of Greek Literature factored in as well.) By shrewdly appealing to Everett’s reputation as a prominent public speaker (who could keep his oratorical skills in tune by lecturing on international law and diplomacy at the Law School), U.S. Sen. Daniel Webster (Whig-Mass.) persuaded Everett to take the job. He lived to regret it.

Students rained down a storm of clever pranks that swamped his patience – and Everett was not one to suffer in silence. “When I was asked to come to this university, I supposed I was to be at the head of the largest and most famous institution of learning in America,” he declared one day at Morning Prayers. “I have been disappointed. I find myself the sub-master of an ill-disciplined school.”

At Everett’s behest, the institution officially became the “University at Cambridge,” with nary a breath of “Harvard.” Everett also lost no time in getting the Harvard Corporation to abolish the recently adopted VERITAS motto and reinstate CHRISTO ET ECCLESIAE. (Alumni raged over this until 1885, when VERITAS prevailed.) When the City of Cambridge incorporated in 1846, Everett designed the municipal seal, featuring the image of Gore Hall (1841-1913), home of the College Library and a local landmark.

Despite its brevity, Everett’s term brought a major research component to the University: the Lawrence Scientific School, funded in 1847 by merchant-manufacturer Abbott Lawrence and opened in 1850. The School awarded its last degrees in 1910. The building itself survived until May 7, 1970, when fire claimed it on a site now occupied by the Science Center.

Everett began talking about resigning in 1847. In the following year, he wrote a letter of resignation, which was accepted on Feb. 1, 1849. Everett departed as the ninth and final President to live in Wadsworth House. In 1852, he became U.S. secretary of state in the Fillmore administration. He later ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. vice presidency.

At the dedication of Gettysburg National Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1863, Everett delivered a two-hour principal address, remembered now, if at all, as the upbeat to a two-minute speech by the 16th president of the United States.

Term of office: 1829-1845

On June 2, 1829, the University grandly installed Josiah Quincy (1772-1864) as its 15th president. The dazzling Commencement Day ceremony proved a false harbinger. For if John Thornton Kirkland was Harvard’s best-loved chief executive, Josiah Quincy soon plummeted to the opposite pole.

According to his son, Quincy had hoped to create a Harvard that produced “high-minded, high-principled, well-taught, well-conducted, well-bred gentlemen.” Unfortunately, Quincy never got his finger on the inner pulse of student life. Within five years, his rough touch tripped off one of the most destructive and divisive student disorders in Harvard history.

During the winter of 1833-34, an argument between a student and a tutor (possibly a professor) prompted disciplinary action against several students. Classmates protested in word and deed, breaking the tutor’s windows and furniture, and ringing the College bell at night. By May 29, the College felt compelled to send the entire sophomore Class home.

Having found no one to charge for some $300 in window damage, Quincy called on the Middlesex County grand jury to investigate. The interjection of outside authority proved a fatal violation of ancient academic protocol. The ensuing student riots produced mounds of broken glass and furniture, bomb damage in the chapel, a black flag fluttering over Holworthy Hall, and an effigy of Quincy dangling from the Rebellion Tree (so designated by student rioters of 1818). The grand-jury investigation yielded no actionable results. Undergraduate enrollment nosedived, as many existing students left and prospective students looked elsewhere.

To make matters worse, Quincy took the grading system (introduced by the reforms of 1825) and transformed it into a rigid and much-hated “Scale of Merit,” which consisted of an eight-point spread applied to every recitation in class, with various demerits for behavioral infractions. Quincy himself kept score.

On the positive side, Quincy championed academic freedom and produced a valuable “History of Harvard University” (1840). While researching this two-volume work in the Harvard Archives, Quincy discovered an original sketch of the VERITAS seal in College record books from the winter of 1643-44. For reasons unknown, the motto had never before been used. Meanwhile, Harvard had adopted two other mottoes. Atop a huge tent in the Yard on Sept. 8, 1836, a white banner publicly displayed the VERITAS seal for the first time during the Harvard Bicentennial (which also brought the first singing of “Fair Harvard”). The Harvard Corporation officially adopted the motto in 1843, setting off a four-decade tug of war between VERITAS (“Truth”) and the previous motto CHRISTO ET ECCLESIAE (“For Christ and Church”).

With Quincy’s support, Harvard also established its first research division, the Astronomical Observatory, in 1839. Six years later, Quincy retired and returned to Boston.

Term of office: 1810-1828

By all accounts, John Thornton Kirkland (1770-1840) was a remarkable man whose special touch conjured up a golden age for all who walked the Yard on his watch. He was the epitome of the gentleman scholar. For no other Harvard president have graduates penned so many affectionate tributes.

Writing to President Eliot in 1871, historian-diplomat George Bancroft, Class of 1817, recalled that among all the various individuals who had crossed his path, he had encountered “few who were [Kirkland’s] equals, and no one who knew better than he how to deal with his fellow-men. [. . .] There was not in his nature a trace of anything that was mean or narrow. [. . .] He opened the ways through which [the University] has passed onward to its present eminent condition [. . .].”

Leading by example came second nature to Kirkland. Even as a Harvard tutor (1792-1794), he adopted the then-unorthodox approach of treating students as gentlemen in hopes of inspiring them to become gentlemen. Kirkland left no significant literary legacy. Yet his own virtues – clarity and imagination of thought, charm in conversation, sensitivity to beautiful language, and more – inspired an outpouring of student writing.

Despite Kirkland’s polished manner, the Yard (which Kirkland did much to enhance) was not entirely placid. One Sunday evening in 1818, a fierce food fight broke out in recently built University Hall (then partly used as commons for all four Classes). The disciplining of four sophomores prompted classmates (including Ralph Waldo Emerson) to swear allegiance against such “tyranny” under a Rebellion Tree.

In spring 1823, the Great Rebellion – a much more complex student uprising – put institutional reform on the front burner. Accordingly, in 1825, the University adopted 13 chapters of Statutes and Laws that changed the curriculum, the classroom (including the introduction of sections and grades), and faculty structure. The new laws also required the president to deliver an annual report to the Board of Overseers. Also, the Kirkland years saw the establishment of two professional schools – Divinity (1816) and Law (1817) – as well as the completion of Divinity Hall (1826), Harvard’s first Cambridge building outside the Yard.

Kirkland’s undoing began in 1826 when newly elected Corporation Fellow Nathaniel Bowditch launched a review that found Harvard a fiscal fiasco. The Corporation approved wide-ranging economies, including docked pay for the president and pay cuts for professors. In 1827, Kirkland suffered a paralytic stroke. On March 27, 1828, his fiscal nonchalance finally provoked a tongue-lashing from Bowditch. To everyone’s surprise and dismay, Kirkland resigned the next day. Heartbroken seniors penned him a farewell encomium of unexampled love and gratitude.

Term of office: 1806-1810

In the 18 months following the death of Joseph Willard, an epochal change swept through the University as liberal-minded Unitarians captured both the Hollis Professorship of Divinity (the institution’s oldest endowed chair) and the presidency. The new Hollis Professor was Henry Ware, Class of 1785. The new president was Samuel Webber (1759-1810) (himself rising from Harvard’s second oldest chair, the Hollis Professorship of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy).

“The Unitarian victory in this double trial of strength, a logical outcome of the liberal tradition that had been slowly gathering momentum since the days of [John] Leverett and [William] Brattle [influential tutors during the Mather administration, with Leverett later becoming president in his own right], was [. . .] momentous. It ranks with the election of Charles W. Eliot in 1869, and the tipping out of Increase Mather in 1701, as one of the most important decisions in the history of the University. Orthodox Calvinists of the true puritan tradition now became open enemies to Harvard. [. . .] On the positive side, the effect was far-reaching. Unitarianism of the Boston stamp was not a fixed dogma, but a point of view that was receptive, searching, inquiring, and yet devout; a half-way house to the rationalistic and scientific point of view, yet a house built so reverently that the academic wayfarer could seldom forget that he had sojourned in a House of God.” (Samuel Eliot Morison, “Three Centuries of Harvard”)

Death claimed Webber on July 17, 1810, after just four years in office – too short a span in which to realize ambitious hopes such as building an astronomical observatory. But through his election alone, Webber cast shadows far longer than he could have imagined.

What’s in a name?

Wadsworth House

Named for Harvard President Benjamin Wadsworth, Wadsworth House is the second oldest building at Harvard. General George Washington set up his first Massachusetts headquarters in the house while in command of the Revolutionary troops.

1700s

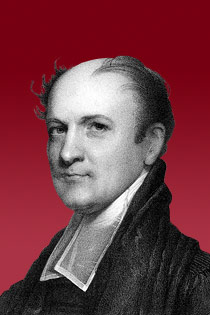

Term of office: 1781-1804

Almost 13 months after Samuel Langdon’s resignation (August 1780), Harvard finally found a new president in Joseph Willard (1738-1804), whom historian Samuel Eliot Morison has pronounced successful if not great. After the short terms of his two immediate predecessors, Willard’s longevity in office alone qualifies as no small measure of success.

A far more substantive example is the founding of the Harvard Medical School in September 1782. The “Medical Institution of Harvard University” was the first faculty beyond the College. (Ironically, Willard had once aspired to become a physician.) While there are substantial grounds for considering Harvard a university even in the 17th century, the new professional school unquestionably made Harvard a university in every modern sense. (First based in Cambridge, the Medical School moved to Boston in 1810.)

Important changes also came to the undergraduate scene. Only a few weeks before Willard’s election, students formed the Harvard Chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society, which held its first Literary Exercises in 1782. PBK was only one of the many groups in which the period abounded. In 1787, French teacher Joseph Nancrède became Harvard’s first paid instructor in a modern language. (Before Nancrède’s arrival, students wishing to learn French had to use licensed outside teachers.)

Less happily for students, the Harvard Corporation tried to lessen competitive dressing in 1786 by imposing a student dress code that banned silk outright. The code further prescribed blue-gray coats and four approved colors of waistcoats and breeches, along with particulars of dress tied to one’s year in school (e.g., varied ornamental details down to the buttonholes – but nothing in gold or silver, thank you!). Students detested these onerous requirements and the punishments incurred for transgressing them.

Willard’s own sense of decorum required that students and tutors doff their hats when he entered the Yard. Such traditional formality extended to his personal contacts with students and made him seem rigid to many. Nevertheless, in 1799, Willard broke with tradition by giving his Commencement address in English instead of Latin – the first known example of a Harvard president’s use of the native tongue for this purpose.

Born in Maine, Willard showed an early knack for mathematics and navigation. He once planned on going to sea and retained a lifelong interest in science. Academically, he was a late bloomer, finishing his undergraduate degree in his late 20s. Before becoming Harvard’s chief executive, he served as the College butler, a tutor in Greek, and a Fellow of the Corporation. Willard died in office on Sept. 25, 1804.

Term of office: 1774-1780

After the mysterious resignation of Samuel Locke, the mantle of the presidency came to rest upon the shoulders of Samuel Langdon (1723-1797), whose term covered most of the Revolutionary era.

For Harvard, the greatest disruption of the age came shortly after the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. On May 1, the Committee of Safety ordered the College to close early as Cambridge turned into an armed camp, with soldiers of the Revolution soon billeted in four Harvard buildings (Holden Chapel, Massachusetts and Hollis halls, and Stoughton College [dismantled in 1781]). Gen. George Washington briefly set up headquarters in Wadsworth House, and a thousand pounds of lead that had once repelled rain and snow on the roof of Harvard Hall went to deadly new use as bullets repelling British troops in Boston.

By September 1775, the Harvard Corporation had decided to resume academic life in Concord. In June 1776, three months after British troops left Boston, the College received permission to return to Cambridge. During the winter of 1777-78, a second physical displacement loomed, when the Continental Army needed quarters for British prisoners of war: Gen. John Burgoyne and his troops, recently captured at Saratoga, N.Y. (Burgoyne and his staff occupied Apthorp House, then a commandeered property and now the master’s residence of Adams House.) Students had to leave Harvard for three months while other arrangements were eventually made.

Amid this epic turmoil, Langdon presided over a much-diminished academic realm. From 1774 to 1780, the Corporation suspended public Commencements. Enrollment declined, and disrupted commerce led to one shortage after another, from books to bread. Harvard finances fared no better.

Langdon’s Revolutionary fervor had made a favorable impression early on. (He had even prayed over the army on the night before the Battle of Bunker Hill.) But his words and deeds soon irritated students no end, what with scriptural harangues stretching to 90 minutes at the expense of Sunday-evening singing.

Things came to a head in summer 1780, when students petitioned the Corporation for Langdon’s dismissal. Langdon admitted his presidential unsuitability and promised to resign. He did so on Aug. 30.

Term of office: 1770-1773

Samuel Locke (1732-1778) entered the presidency with every promise of becoming a great academic executive. No less a contemporary than Yale President Ezra Stiles deemed him “a man of strength, penetration, and judgment, superior to Holyoke in everything except classical learning and personal dignity,” in the words of Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison.

Most of Locke’s contemporaries thus found themselves at a loss to understand his resignation of Dec. 1, 1773 – not least because the Harvard Corporation volunteered no details in its bare-bones announcement. It took the 20th-century publication of Stiles’ diary to bring the reason to light: Locke had fathered a child by one of his maids. “Mr. Locke took the blame, retired to the country, and was promptly forgotten.” (Morison)

Term of office: 1737-1769

The presidency of Edward Holyoke (1689-1769) brought many distinctive features to Harvard that endure to this day. The earliest evidence for the singing of the now-traditional Commencement hymn (a setting of Psalm 78: “Give ear, my children“) comes from Holyoke’s 1737 installation. Two venerable Harvard structures arose during his term: Holden Chapel (1744) and Hollis Hall (1763). A third, Old Harvard Hall, was lost to fire in 1764 (along with nearly all the College library and scientific equipment housed within its walls). The main portion of today’s Harvard Hall replaced it in 1766.

And who bought that bizarre bit of Jacobean furniture now known as the President’s Chair? None other than Holyoke himself (who readily confessed his own ignorance of its history). The chair literally bears Holyoke’s personal impress, for he made the large oak pommels perched atop its front posts. Aptly enough, Holyoke was the first of several Harvard presidents to have his formal portrait painted while seated in this chair.

Holyoke served for just over 32 years, making his the second-longest presidency in Harvard history (only Eliot’s 40-year term was longer). Many Harvard alumni from New England who played important roles in the American Revolutionary War were educated during his relatively liberal administration. (At least as early as the 1720s, the winds of revolution had begun to blow through Commencement debates. Analysis of the nature and function of government gathered momentum in debates of succeeding decades.)

In both the humanities and the sciences, the curriculum underwent modernization, from the adoption of contemporary texts to the introduction of better science equipment and instruction. Holyoke openly supported the work of John Winthrop, the Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, who established the first experimental-physics laboratory in what is now the United States. A series of spring and fall public “exhibitions” (debates, dialogs, and orations) by upperclassmen began in 1756 and continued for more than a century.

Most crucial of all was the revamping of the old educational system under which a single tutor taught all subjects to a given class. In January 1767, tutors began to specialize by teaching only a limited number of subjects.

On June 1, 1769, shortly before his 80th birthday, this oldest of all Harvard presidents left his final distinctive mark. Speaking from his deathbed, Holyoke uttered an insight that still resonates in the ears of his successors: “If any man wishes to be humbled and mortified, let him become President of Harvard College.”

Term of office: 1725-1737

After the death of John Leverett, the Harvard Corporation offered the presidency to two ministers who declined the invitation. Finally, in June 1725, the Corporation elected Benjamin Wadsworth (1670-1737), one of their own number, who took the job more dutifully than joyfully.

With £1,000 from the Massachusetts Great and General Court, the College soon built a new President’s House on the southern end of the Yard. Wadsworth began living there in November 1726, before the structure was completed in the following year. Today, Wadsworth House, which served as Harvard’s executive residence until the end of the Everett administration in 1849, is Harvard’s second-oldest building.

Under Wadsworth, the Harvard Governing Boards produced a new set of College laws in 1734 (the first major revision since 1692), and the curriculum was improved. Student behavior, however, did not follow suit. “Wadsworth was no disciplinarian, and the young men resented a puritan restraint that was fast becoming obsolete. The faculty records, which begin with Wadsworth’s administration, are full of ‘drinking frolicks,’ poultry-stealing, profane cursing and swearing, card-playing, live snakes in tutors’ chambers, bringing ‘Rhum’ into college rooms, and ‘shamefull and scandalous Routs and Noises for sundry nights in the College Yard.’“ (Samuel Eliot Morison)

In 1727, London merchant Thomas Hollis established the Hollis Professorship of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, Harvard’s second named chair. Six years earlier, Hollis had given the College its first endowed position (in divinity).

Kindly and intelligent, Wadsworth was “faithful, devoted, and methodical,” Morison reports. “He combed the records for evidence of college property, and did his best to recover lands alienated through the neglect of college officers or the enterprise of squatters.” He died in office on March 27, 1737 (= March 16, 1736, in the Julian calendar then used by English colonists).

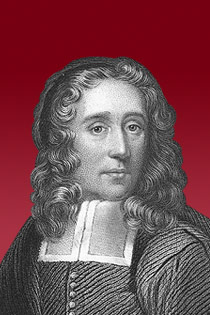

Term of office: 1708-1724

For nearly six years (1701-1707) after the departure of Increase Mather, Harvard’s chief presiding officer was Vice President Samuel Willard, who resigned because of illness in August 1707 and died in the fall. The presidential installation of John Leverett (1662-1724) in January 1708 marked the end of more than 35 years of institutional instability tracing back to the days of Leonard Hoar.

Leverett was Harvard’s first secular president. With his extensive and varied background in public life, he loomed large, both in and beyond the Yard. He had also taught during the Mather administration (1685-1697) and served as a Fellow of the Harvard Corporation (1685-1700, 1707).

The new president immediately set about ensuring that the College received its due from various bequests. While the curriculum remained virtually unchanged, enrollment soon began to grow. By November 1718, Harvard had 124 resident students, including resident graduates and those staying on to earn a master’s degree. Massachusetts Hall – Harvard’s oldest surviving structure, built as a dormitory in 1720 – dates from this period.

During the Leverett era, the College’s first endowed chair (the Hollis Professorship of Divinity, 1721) was established, the first student club came into being (1719), and the first student publication (“The Telltale,” 1721) appeared. According to Leverett’s diary, the faculty struggled mightily to control unsavory student behavior such as swearing, “riotous Actions,” and card-playing – to which student diaries add attending horse races and pirate hangings in Boston.

Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison offers this capsule summary of the period: “Leverett took the presidency when Harvard was weak and disorganized, after a generation of charter-mongering and of non-resident presidents. He put her finances on a firm basis, and obtained her first endowed chair. But his service to the College and the country lies more in the principles that he maintained and the precedents that he established, than in positive accomplishments. In an era of political and sectarian strife, he was steadfast in preserving the College from the devastating control of a provincial orthodoxy. He kept it a house of learning under the spirit of religion, not, as the Mathers and their kind would have had it, the divinity school of a particular sect. Leverett, in a word, founded the liberal tradition of Harvard University.”

He died in office on May 14, 1724 (= May 3 in the Julian calendar then used by English colonists). Remembering Leverett after his death, Cambridge minister Nathaniel Appleton hailed him as a “great and generous Soul” who was divinely destined for distinction.

What’s in a name?

Dunster House

Named in honor of Henry Dunster, who became the first president of Harvard College immediately after his arrival in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay in 1640. When he left the College in 1654, it had become a well-established institution.

1600s

Term of office: Acting President, 1685-1686; Rector (a unique title), 1686-1692; President, 1692-1701

Increase Mather (1639-1723) had been the Governing Boards’ first choice to succeed Urian Oakes. After the death of John Rogers, however, the job offer first went to Joshua Moody, a minister from Portsmouth, N.H. Moody declined. The second possibility, one Michael Wigglesworth, promptly removed himself from consideration.

Not until March 1685 did the Corporation offer the position of president pro tempore to Mather. He might with equal justice have been declared “president in absentia,” for in the 16 years during which Mather headed the College under three distinct titles, he spent mere months living in Cambridge. Mather commuted by ferry to Cambridge from his home in Boston’s North End, where he continued to serve his congregation. Indeed, during the last four years of his rectorship, Mather was not even in the country, much less in Cambridge: he was engaged in political lobbying in England.

To make matters even more tenuous, a court decision had voided and vacated the Royal Charter for Massachusetts Bay Colony in October 1684, thus uprooting many legal arrangements made under the old charter. For the College, this meant that the Charter of 1650, the document that created the Harvard Corporation, was in legal limbo at best and defunct at worst.

Shortly after Mather returned to Boston in May 1692, the Charter of 1650 enjoyed a brief restoration. “Mather brought to Boston a new Province Charter for Massachusetts Bay, and the new General Court proceeded to reincorporate the College,” as Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison explains. “In this, as in several subsequent short-lived college charters, Mather’s object was to keep the College under control of the Congregational Church, and free of political influence.”

For the duration of Mather’s presidency, power struggles raged back and forth across the Atlantic over the crafting of a College charter that could balance colonial desires for autonomy against royal demands for control. A small flotilla of charters real and imagined all sank beneath the waves.

Finally in 1701, Mather’s political rivals in Boston got the upper hand and pushed him out on a technicality. The General Court gave Mather an ultimatum: resign the ministry and move to Cambridge, or give up the presidency. In midsummer, having spent six most unpleasant months in Cambridge, Mather fled back across the Charles, where his congregation welcomed him with open arms. Considering the presidency thus vacated, the General Court put Samuel Willard in charge as vice president of the College.

In July 1702, Mather himself confessed to his diary that “[t]he Colledge is in a miserable state. [. . .] The Lord pardon me in that I did no more good whilest related to that society.”

Term of office: 1682-1684

After the death of President Urian Oakes, Increase Mather promptly emerged as the first-choice successor. But Mather was not yet to rule the Harvard roost: his church would not release him from his pastoral obligations. Another candidate was offered the job. He too declined.

Finally in spring 1682, the Governing Boards found a willing choice in John Rogers (1630-1684), who at age 6 had crossed the Atlantic with his parents to settle in New England. Cotton Mather remembered Rogers as a sweet-tempered, genuinely pious, and accomplished gentleman given to long-windedness at daily prayers. With such personal charm and character, Rogers “might well have made a successful president,” in the estimation of Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison.

But through no fault of his own, Rogers continued the disruptive trend set in motion during the Hoar administration (1672-1675). Whatever his presidential gifts, Rogers had no chance to display them. Little more than two years after his election, he died most inauspiciously on July 12, 1684 (the day after Commencement; = July 2 in the Julian calendar then used by English colonists), during a total solar eclipse.

Term of office: 1680-1681

In April 1675, a few weeks after Leonard Hoar’s resignation in March, Urian Oakes (ca. 1631-1681) agreed to take the position of president pro tempore. This acting presidency persisted for five years. With no better candidate having come forward, the Harvard Governing Boards finally gave Oakes the full title in February 1680. In early June, Oakes overcame his reluctance and accepted the new role. The delay proved ill timed: Oakes died in office on Aug. 4, 1681 (= July 25 in the Julian calendar then used by English colonists). Many feared that the institution had little chance of surviving much longer.

Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison describes Oakes as “a little bit of a man, cram-full of learning, intolerance, and choler. No mean poet in English, and a writer of vigorous prose, he has left on record a series of lengthy Latin Commencement orations that are models of academic punning and classical wit.” Indeed, Cotton Mather hailed Oakes as the greatest “Master of the true, pure, Ciceronian Latin and Language” in the land.

The Oakes years saw the completion of Old Harvard Hall in 1677 as a replacement for “Old College” (Harvard’s short-lived first new building at the southern end of the Yard; fire destroyed Old Harvard in 1764).

Term of office: 1672-1675

By the time Leonard Hoar (ca. 1630-1675) became president in 1672, Harvard had lasted long enough to produce homegrown leadership. Not until the 1971 arrival of Derek Bok, who holds a Harvard law degree, would there be a Harvard chief executive who, like the first two presidents, had not been educated at the College.

Hoar took office with every hope of transforming Harvard into a major research institution, complete with chemical laboratories, a botanical garden and an agricultural-research station, and a mechanical workshop – all outlined in a letter of December 1672 to Robert Boyle, the eminent British chemist and physicist. But so grand an enterprise was not to flower in full until the 19th century.

The detailed reasons for Hoar’s brief presidency have remained obscure: historian Samuel Eliot Morison notes that while everyone on the local scene talked about Hoar, little definitive evidence got committed to paper. It seems clear, however, that both his personality and actions proved unacceptable to too many. Students mocked his words and deeds, and tutors resigned in disgust. At one point, Hoar’s heavy-handed discipline resulted in the flogging of a student by a jailer who was later removed for cruelty.

Twice (in October 1673 and October 1674), Hoar’s case came before the Great and General Court, with the threat of dismissal hanging in the balance. By the winter of 1674-75, conditions had degenerated to the point that the entire student body walked out. In March 1675, Hoar resigned. Utterly broken in spirit, he died shortly afterwards. More than three centuries later in 1976, at the request of a portrait painter touched by Hoar’s plight, the Massachusetts Senate approved a resolution clearing Hoar of misconduct.

Hoar left behind one quiet but greatly influential innovation: a series of triennial (three-year) catalogs of Harvard graduates listed by their respective Classes. When the first installment of 200 graduates appeared in 1674, it was probably the first list of college or university alumni published anywhere, according to Morison. After 1875, the compendium appeared at five-year intervals. The last “Quinquennial Catalogue” (which also includes all Harvard officers to date) appeared in 1930 and remains a prime reference on the 65,584 individuals who had thus far received Harvard degrees.

Term of office: 1654-1672